SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

The lawmaker raised his voice and forcefully pointed his finger: “The Senate has been an obstructionist Senate!”

It was February 26, and Cagayan de Oro 2nd District Representative Rufus Rodriguez was delivering an impassioned speech at the House of Representatives on a “fourth mode” of amending the Constitution.

Rodriguez said House lawmakers now want to follow the “Bernas proposal” in amending the Constitution, “because the Senate does not even want to meet with us.”

The Constitution describes three modes by which amendments or revisions can be proposed: first, through Congress convened as a constituent assembly (Con-Ass); second, through a constitutional convention (Con-Con) with appointed or elected members; and third, through a people’s initiative (PI) where a petition is made by at least 12% of registered voters.

The so-called fourth mode, the Bernas formula, seeks to amend the Constitution by using the process of crafting a regular law: a bill is filed in either the House of Representatives or the Senate, the chamber deliberates and votes on it, then sends it to the other house to undergo a similar procedure, then the two houses thresh out differences and approve the measure.

Like the House lawmakers, in the upper chamber, one senator recently invoked the same name: “Bernas.”

It was “the late constitutionalist Father Joaquin Bernas, who was also a member of the Constitutional Commission that drafted the present Constitution,” who suggested this “fourth mode” of charter change, said Senator Francis Tolentino in proposed Senate Resolution No. 941 on adopting rules to amend or revise the charter.

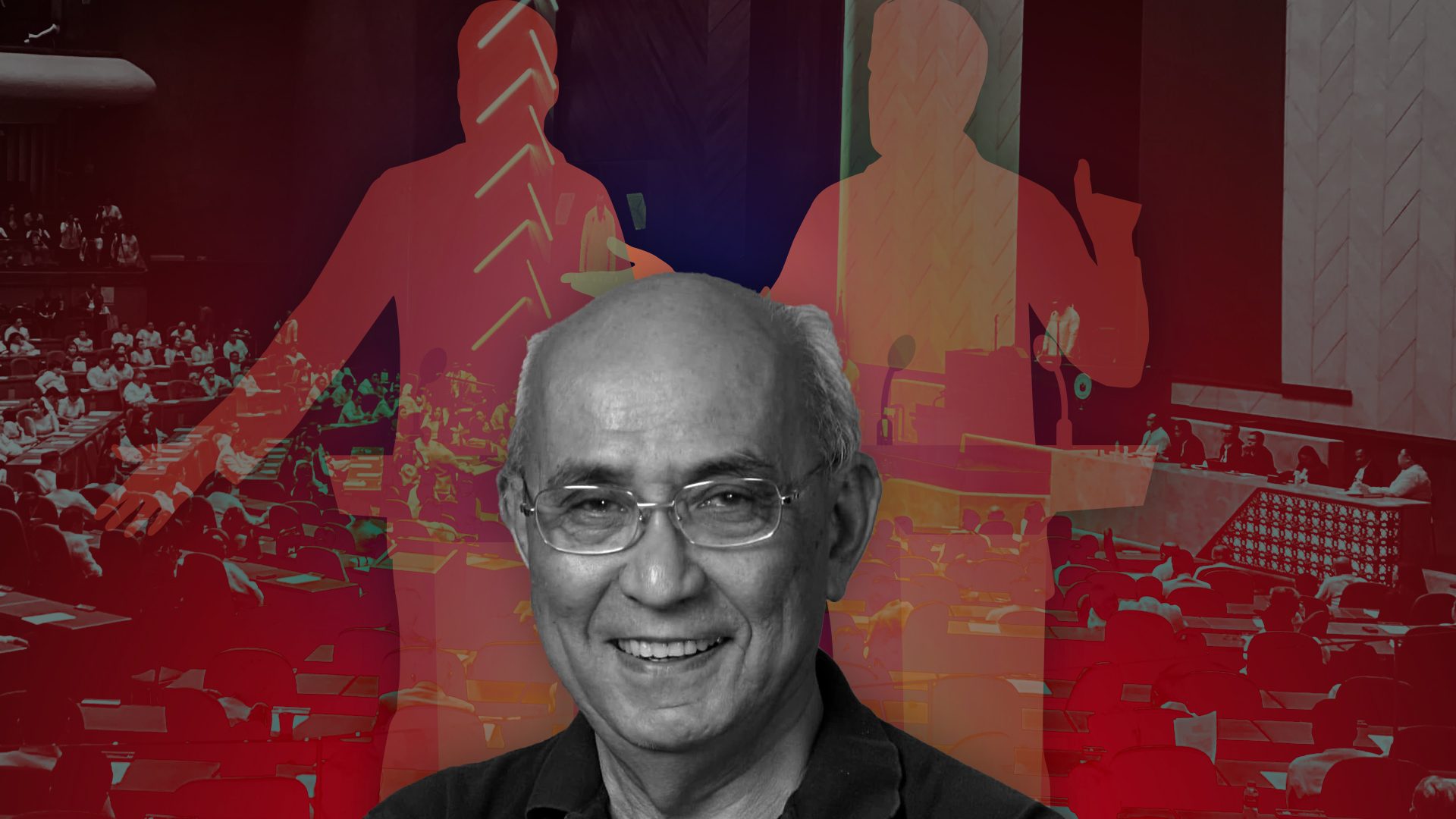

It has been exactly three years since he died of heart ailments at the age of 88 on March 6, 2021. Yet the name of Father Joaquin Bernas SJ, one of the nation’s greatest legal minds, still reverberates in the halls of Congress. In fact, if the Bernas formula is used and later challenged at the Supreme Court, then his voice – through his writings – will be heard in Padre Faura once more.

Who is Father Bernas, and why does he matter in the debate on charter change?

Respected by the Supreme Court

Born in Baao, Camarines Sur, on July 8, 1932, Bernas was the second in a family of 12 children. “Bernie” to his fellow Jesuits and “Father B” to his students, he was known as “Quining” to his relatives.

Bernas entered the seminary of the Jesuit religious order at the age of 17. His father died six months after he joined the Jesuits, according to his nephew Luigi Bernas, and this prompted him to ask his superior – without his mother’s knowledge – if he could leave the seminary so that he could help his family.

Bernas’ novice master “replied by telling to him to forget the idea and stay put where he was, because he would only be a burden to his mother and family,” his nephew said in a eulogy.

He eventually finished college at Berchmans College in Cebu and studied law – graduating as class valedictorian – at Ateneo de Manila. He placed ninth in the Bar exam, then earned his master of laws and doctor of juridical science degrees at New York University.

Most of his assignments later evolved around the Ateneo Law School, where he was dean from 1972 to 1976, and then from 2000 to 2004, and Ateneo de Manila University, which he led as 28th president from 1984 to 1993. He was Ateneo president when dictator Ferdinand E. Marcos was ousted in a peaceful revolt in 1986.

He also led the Jesuit order in the Philippines from 1976 to 1982, midway through the Marcos dictatorship. Many Jesuits, at that time, were at the forefront of fighting the dictator.

His knowledge, integrity, and leadership made him a highly revered figure in the Philippines. Supreme Court (SC) magistrates sought his counsel, lawyers bowed to his wisdom, and journalists ran to him for help to digest legal concepts for a mass audience.

And politicians, to this day, invoke his words for their various purposes.

“Even the Supreme Court recognized his authority. Why? Because every time a very difficult question of constitutional law will arise or will be confronted by the Supreme Court, you can be sure that Father Bernas will be called upon to be an amicus curiae (friend of the court),” said lawyer Mel Sta. Maria, who has taught at the Ateneo Law School for more than 35 years.

Sta. Maria cited the 2003 case of Francisco et al. vs. House of Representatives, where petitioners challenged the filing of a second impeachment complaint against then-chief justice Hilario Davide in a span of one year.

Bernas was one of the amici curiae summoned by the Supreme Court. “When Bernas decided to stand up and sort of lecture the Supreme Court and ask questions to the Supreme Court, and once he finished, the audience could not resist applauding,” Sta. Maria told Rappler in a mix of English and Filipino.

“Silence, silence, silence!” was all the court could say, as the audience applauded the constitutionalist.

The SC, in its decision declaring the second Davide impeachment complaint unconstitutional, later cited “the august words of amicus curiae Father Bernas.”

“It says a lot,” said Sta. Maria. “Bow sila kay Bernas (They really bowed to Bernas).”

Former chief justice Artemio Panganiban Jr., in fact, “had said in a public forum that no discussion on constitutional issues would be complete until we hear from Father Bernas,” wrote former Ateneo Law School dean Cesar Villanueva in a tribute in the Ateneo Law Journal.

Santa Maria quickly added, however, that Bernas stayed “very humble.”

He was a priest, after all.

A priest before anything else

Reading the 144-page special issue of the Ateneo Law Journal in honor of Bernas in July 2022, one gets the same impression from his family and friends: despite his achievements, being a constitutionalist or a law professor was secondary to him.

Sta. Maria said, “When you ask him, ‘Father, who are you?’ He will say, ‘I’m a professor, I love being a professor. Others say I am a constitutionalist. Well, I am a columnist.’ But what he will really say is, ‘But first and foremost, I am a priest.’”

Bernas’ successor as Ateneo president in the 1990s, Father Bienvenido Nebres, said the late Jesuit was “remembered for his scholarly lectures, books, and elegant and witty speeches, but as well for his Masses and his short – very short – memorable homilies.”

His fellow Jesuits treasured Bernas’ retreats and spiritual guidance, Nebres added at Bernas’ funeral Mass.

“Father Bernas was first and foremost God’s good servant. In everything he did, Father Bernas always placed God at front and center,” wrote Ateneo law professor Eugene Kaw in an obituary published by Rappler in March 2021.

“That certainly explains one of the best traits of Father Bernas: how he could deepen everyone’s faith through crisp and provocative homilies three to five sentences long, lasting no more than five minutes,” he said.

Kaw added it was the word “vocation” that best describes Bernas’ life. Each of his life milestones, in fact, “has been about the preparation for and fulfillment of that vocation.”

“He dedicated his entire life to the service of others – a path that he always recognized as having been chosen by God. In one of his succinct homilies, Father Bernas shared: ‘Vocation is a word which we sometimes reserve for a call to convent life or priestly life. It is not that way at all. Vocation is for all, yes, even for rascals. God singles out each one of us for a task.’”

‘Christ came to save not souls, but people’

In a 2006 interview with Alya Honasan for the Sunday Inquirer Magazine, Bernas himself opened up on his deepest convictions.

“The reason why I’m teaching law is because of our Lord, who came to save sinners,” Bernas said in this Inquirer interview.

He then addressed criticism that he is friends with people like Lucio Tan, a crony of the late dictator Marcos, and deposed former president Joseph “Erap” Estrada, who was convicted of plunder in 2007.

“People criticize my having friends like Lucio Tan and Erap, who don’t have very saintly reputations. Our Lord hung around with Pharisees. If I had lost faith, I would have abandoned law school!” Bernas said.

“You have to have a sense of humor, and accept that there are some things you cannot do anything about, even if you try. It is messy, and I see a lot of corruption, bribery. I don’t really lose sleep over things I cannot achieve, because I’m not God. I realized that long ago,” he continued.

Why did he join the Jesuits? Bernas said it was “because I wanted to become a priest and something else.”

He was referring to how many Jesuits study fields of expertise other than theology and philosophy – including law, climate change, and astronomy – so that they can better engage the world outside the usual church buildings. Pope Francis, himself a Jesuit, has a background in chemistry. Jesuits, who emphasize “finding God in all things,” call themselves “contemplatives in action.”

“I didn’t want to be confined to the sacristy, because I feel the role of the priest and the Church in general is both spiritual and worldly,” Bernas said.

“Christ came to save not souls, but people, and people are body and soul. He was curing the sick, feeding the hungry. And the thrust of the Church today, which is social justice, is because of the responsibility to care about the material welfare of people also,” the Jesuit constitutionalist added.

The grander ‘Bernas proposal’

Bernas, as a priest, was “very honest,” Sta. Maria said. “The kind of honesty and sincerity which he exhibited while he was a priest, one can also see in his deliberations on matters of law.”

Bernas was also “sensitive” in fighting human rights abuses. This was most evident in how he spoke of the Bill of Rights.

In his sponsorship speech at the Constitutional Convention in 1986, Bernas made an iconic statement: “The protection of fundamental liberties is the essence of constitutional democracy. Protection against whom? Protection against the state.”

Sta. Maria said Bernas, as a constitutionalist, always stressed that when a person looks at the Constitution, “you not only look at its words, but the aspiration of its words and the spirit that it wants to convey to us.”

This brings us back to 2024, when lawmakers are pushing for the “Bernas formula” in changing the charter.

“But where in the Constitution does one find this mode?” asked Bernas in a 2012 opinion piece for the Philippine Daily Inquirer, when Benigno Aquino III was president.

“The elements of this mode are all in Article XVII. The fundamental principle is that what is not prohibited by the Constitution, either explicitly or implicitly, is left to the discretion of Congress provided it can be traced somehow to the powers of Congress. It is clear from Article XVII that the power to propose amendments can only be activated by Congress,” he said.

“The two houses of Congress are not required, as they were under the 1935 Constitution, to be in joint session. Hence, it is quite possible for the two houses to formulate amendments the way they formulate laws – as they are where they are. Once one house is through with a draft, it is passed on to the other house for action,” Bernas added.

Sta. Maria said Bernas, however, always posed a caveat: examine the context.

“This was always the caveat of Bernas: ‘But yet, we have to look at the context of how this is always being made. We have to look at the environment outside, and we have to look at the people doing it,” the lawyer said.

“If one looks at it, according to Bernas, who must be the starting engine? Who is the initiator of the amendment among the three bodies of government? It should not be the President. It is Congress,” Sta. Maria said. “So if you already see that the President seems to be involved in this, hmm, then you have to think twice.”

Current efforts to amend the charter are pushed by allies of President Ferdinand Marcos Jr., who is eyeing a plebiscite on constitutional amendments alongside the 2025 midterm elections. The President’s cousin, House Speaker Martin Romualdez, is said to be the main proponent of charter change moves, upsetting presidential sister Imee Marcos.

The bigger picture, in understanding Bernas and the Constitution, lies in the reason why the 1987 charter exists.

It was, in the first place, a fruit of the 1986 EDSA People Power Revolution that deposed the Marcos patriarch and forced the Marcoses into exile in Hawaii.

“When Father Bernas helped frame the 1987 Constitution, he ensured the protection of the Filipino people’s fundamental liberties against government abuses through the Bill of Rights and the system of checks and balances. That was his own way of saying ‘NEVER AGAIN’ to the abuses during the Marcos dictatorship,” Kaw wrote.

Bernas himself, at the 5th Jaime V. Ongpin Memorial Lecture in October 2006, put forward his general conviction on charter change – the grander “Bernas proposal” that lawmakers might do well to consider.

“I have always maintained myself that, for our society, success or failure depends not so much on the system as on the people running the system,” Bernas said. “It is easy to write a Constitution; it is more difficult to make a Constitution work.”

The purpose of a Constitution, added the Jesuit constitutionalist, “is not so much to achieve efficiency as to avoid tyranny in its various varieties.” – with a report from Lance Arevada/Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[The Slingshot] Museology 101 for Andoni Aboitiz](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/TL-Museology-101-Boljoon-Church-panels-March-12-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[Vantage Point] Beware of false prophets: A cautionary examination](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/tl-false-prophet.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=272px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.