SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

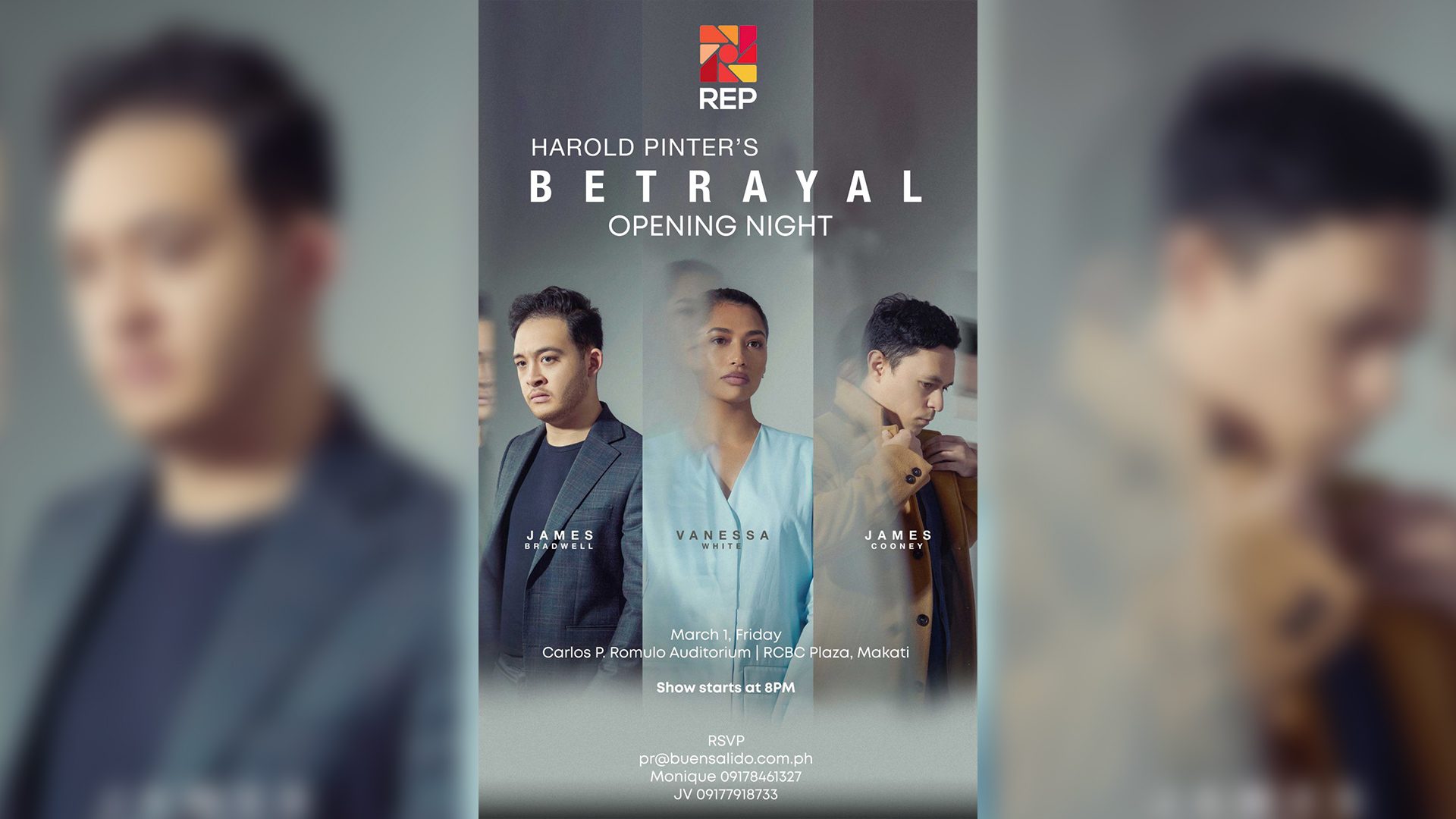

Fifteen minutes after Repertory Philippines’ Betrayal concluded, its cast and artistic team returned to the stage for a Q&A. Over the next 45 minutes, director Victor Lirio and his team explained their process of tackling one of Harold Pinter’s reappraised masterpieces — hoping to turn the historically white and upper-middle-class British text into something that resonated with Filipinos in the country and the diaspora.

It’s not as if the subject is alien. Like many Filipino telenovelas, Betrayal follows a love triangle between three affluent people — gallerist Emma (Vanessa White, from the girl group The Saturdays), her husband and publisher Robert (James Bradwell), and her lover and Robert’s best friend literary agent Jerry (James Cooney) — all of whom are portrayed in this iteration by British actors of Philippine heritage. Pinter’s plays and poetry have always explored, as scholar Dilek İnan noted, “existential alienation in an oppressive world” and who better a subject than the diasporic Filipino — whose histories of in-betweenness, relegation to underpaid and illegal labor, fraught relationships with colonization, and encounters with structural racism remain inescapable despite whatever achievements they accrue.

But as the Q&A progressed, the disconnect between the play in Lirio’s mind and the play we witnessed grew more apparent, paralleling the disconnect in communication between the characters of Betrayal. Lirio tries to tether Pinter’s text to the distinctly Filipino — infusing the material with the subtext of Catholic guilt, diasporic pressures, and issues of transnational identity. Lirio, with set designer Miguel Urbino and scenic artist Julia Pacificador, even goes so far as to create these parallels by decorating the set with licensed reproduction of Pacita Abad’s paintings, made with permission from the Pacita Abad Art Estate. It hits intellectually at deeply interesting places but misses emotionally most of the pain points that make Betrayal echo throughout time. Though ripped directly from Pinter’s life and affair with broadcast journalist Joan Backwell and infused with the personal struggles of its cast and crew, why does this staging of Betrayal feel so polite, discordant, and borderline sterile?

It’s not as if the production is without texture. Bradwell and Cooney, as best friends who compete for Emma’s affection while duping each other, create layered performances out of their men. Cooney is frenetic, less patient, and more emotionally imbalanced as Jerry, whose repeated dismissals of his wife Judith, constant one-sided competition with Robert, and true infantile core come to the fore as the play progresses. Meanwhile, Bradwell manages to de-age Robert across time through his mannerisms — his assured but jaded facade melting away to reveal a more drunken and insidious interior as the play goes back in time. Only Bradwell seems to understand the rhythm of Pinter’s text, the tiny implosions within the pauses that have become the trademark of Betrayal. In these silences, he articulates his hesitation, fears, and exhaustion and through his words, he curates an image worthy of the public standard as a powerful man in the diaspora.

In many instances, Bradwell and Cooney have more chemistry with each other than with White, and most times, one wonders how Emma factors into all of this. In previous iterations of Betrayal, particularly the 1983 film by David Jones and penned by Pinter for the screen, the character’s bravery as an artist was at the forefront, with her status and independence challenging the social mores of the 1960s and 70s, symbolizing a new kind of woman informed but not defined by how British art was radicalized by bombings, trade union strikes, and the growth of the feminist and queer movements in London.

While Lirio makes similar political parallels by temporally shifting the play to the late 2010s to be truthful to the reading of second-generation immigrants struggling through Duterte and Brexit, the influence of these global moments on the characters’ personal lives isn’t as effective or clear, especially because these political fractures appear only through a one-time radio announcement. Throughout the play’s 70-minute stretch, White’s Emma becomes more of a passenger in her own story than the driver of her destiny, and while facts of her character’s life are dropped — her imagined backstory as a curator of Abad’s work at the Saatchi in London, her shared passion for literature with Jerry, and more — so little of her interiority is revealed through White’s acting and behavior.

It’s particularly frustrating because the decision to make Emma the central character in this iteration is so promising. In the Q&A, Regina de Vera, who serves as a cover for Emma, describes the character’s infidelity as an act that stems from a fundamental “undernourishment” in her relationships. It’s an often under-explored point-of-view, the idea that women “stray” as a means of arriving at a healthier, more complete self-identity; as a means of exercising self-agency in a cruel labyrinthine world. It’s an approach that makes sense considering Lirio’s reading because the Filipina has historically been relegated as a caretaker, but rarely has she been cared for in equal measure. It points to a larger cyclicality, a more primal wound rooted in our colonial past. Infidelity, through this lens, is a means of preserving the self.

But we barely get a solid understanding of what sustains Emma’s relationships with the two men throughout the 70 minutes of the play. There is no delight in the intellectual sparring, nor any alchemical pull in privacy with either of her lovers. Their kisses rarely feel ravishing. The confessions barely have weight. Even their arguments — whether during the affair or years after — are without heat. Maybe this emptiness has value in rendering palpable how emotionally inarticulate the characters must be. But it tints the experience with a banality that renders the art inert; that makes the secrets feel as if they weren’t worth keeping in the first place. If the audience cannot see why the two lovers are together, if it is unclear what alternate version becomes accessible to them through the affair, then what is the point?

In Betrayal’s ninth and final scene, Lirio devises a montage close to a mating dance between Emma and Jerry. It is the first scene in the production that inches towards something new — touching on the electricity of pursuing the forbidden, visualizing through lights, choreography, and Max Richter’s reimagining of Vivaldi the freedom infidelity promises. Only in this final moment does Lirio use Pacita Abad’s art as something beyond decoration. Above Emma, Abad’s Paris in the Fall (2003) hangs like a cross in a Catholic church, the light on it growing brighter as she reels from her encounter with Jerry, after almost being caught by Robert. The Endless Blue series was created by Abad after 9/11 and her cancer diagnosis as a testament to how mourning and joy can co-exist through color and abstraction, and Lirio uses Paris in the Fall to punctuate the death of Emma’s marriage with Robert but also the birth of possibility with Jerry; as if Pacita through the painting and across space and time were encouraging her to make a decision that will liberate her from the depths of herself.

It is a glimmer of self-discovery that demonstrates why the production is a classic. Pinter’s text has always centered around how deceit can lead us to a truer version of ourselves and how it is worth pursuing even at the expense of others. But just as things feel as if they’re opening up, just as Lirio and the production are on the precipice of insight, it ends abruptly. By failing to close the gap between its intentions and ambitions, Betrayal lives up to its name. – Rappler.com

Repertory Philippines’ Betrayal runs from March 1 to 17 at the Carlos P. Romulo Theatre in RCBC Plaza.

An earlier version of this review said the paintings used on set were lent to Repertory Philippines by Silverlens Gallery, which may have created the impression that they were the original artworks. Silverlens clarified that those were “not the real artwork by Pacita Abad,” but “licensed reproduction…made with the permission of the Pacita Abad Art Estate.”

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.